#TOUR

Level 0 | James Rickard: Master Carver

The particular interest of Alison and Peter W. Klein in the Polynesian bark cloths has doubtless emerged through their longstanding examination of sculptures by the Aborigines and, as with these sculptures, is accompanied by a personal fascination. Nonetheless, it was not a direct path leading from Australia to the Polynesian Islands and the tapa cloths; rather, their attention was initially drawn to Maori material culture in New Zealand, expressed mainly in carved and painted decoration on buildings or practical objects as well as in body tattoos. In Rotorua, southeast of Auckland on the North Island of New Zealand, they found a contemporary installation in the Maori Arts and Crafts Institute, in which traditional handicrafts still continue today. This was also where they made contact with master carver James Rickard, whom they commissioned to produce a sculpture. It was designed by Rickard as a traditional memorial column and combined with aspects of German history.

Level 1 | Contemporary Painting

Meanwhile, the expectation of the collector couple of finding paintings with pictorial reflections of the traditional culture of the country in New Zealand in the same way as in Australia led them not to traditional artefacts but rather to contemporary works in the visual arts.

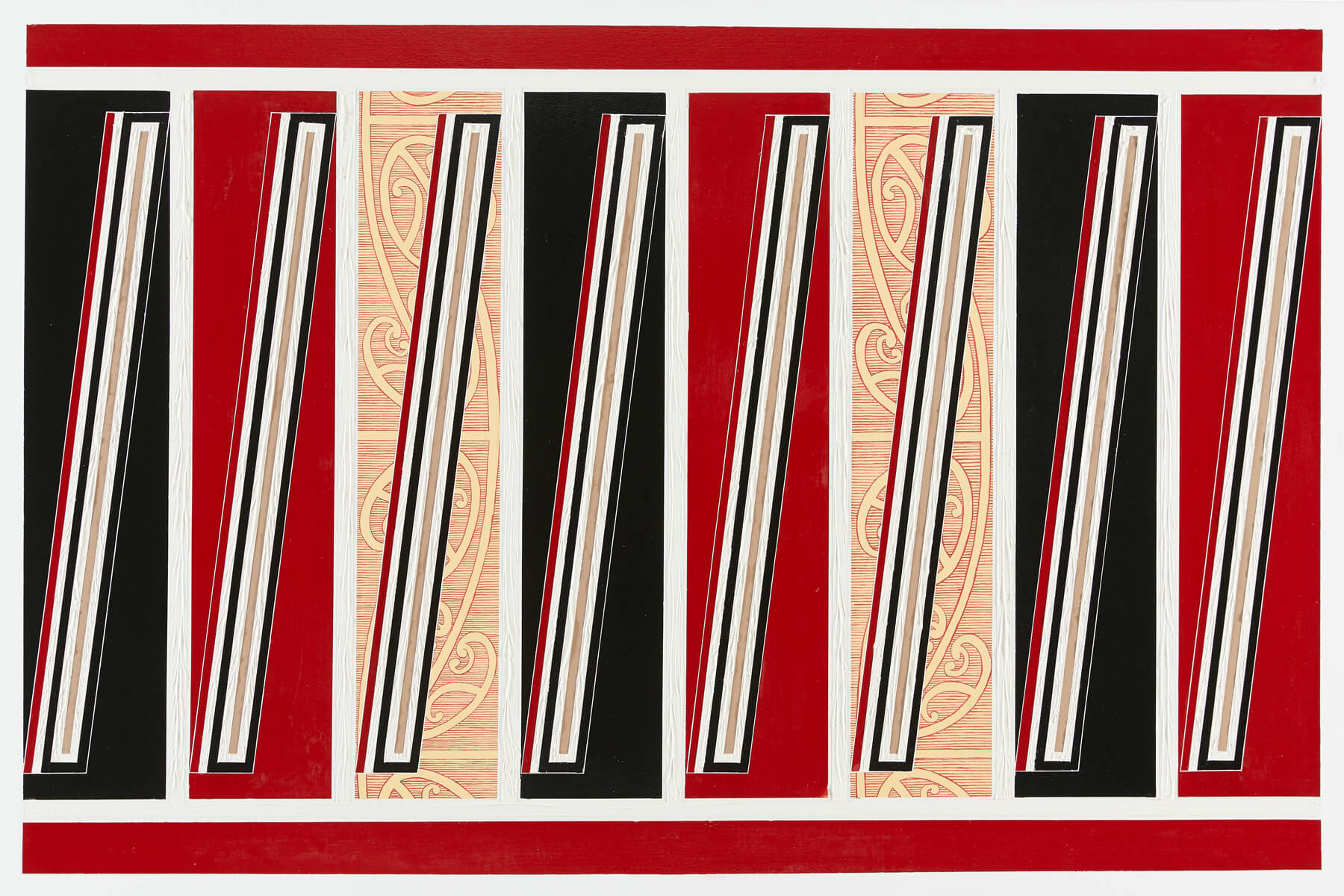

Darryn George (*1970) was born in Christchurch in New Zealand and belongs to the Maori Napuhi tribe. In his academic training, he devoted himself to the western abstract painting tradition. Only as his studies progressed did he conceptually incorporate his bicultural identity into his work. Since 2003, he has exhibited paintings in which he combines abstract painting as well as artistic and linguistic elements of Maori culture.

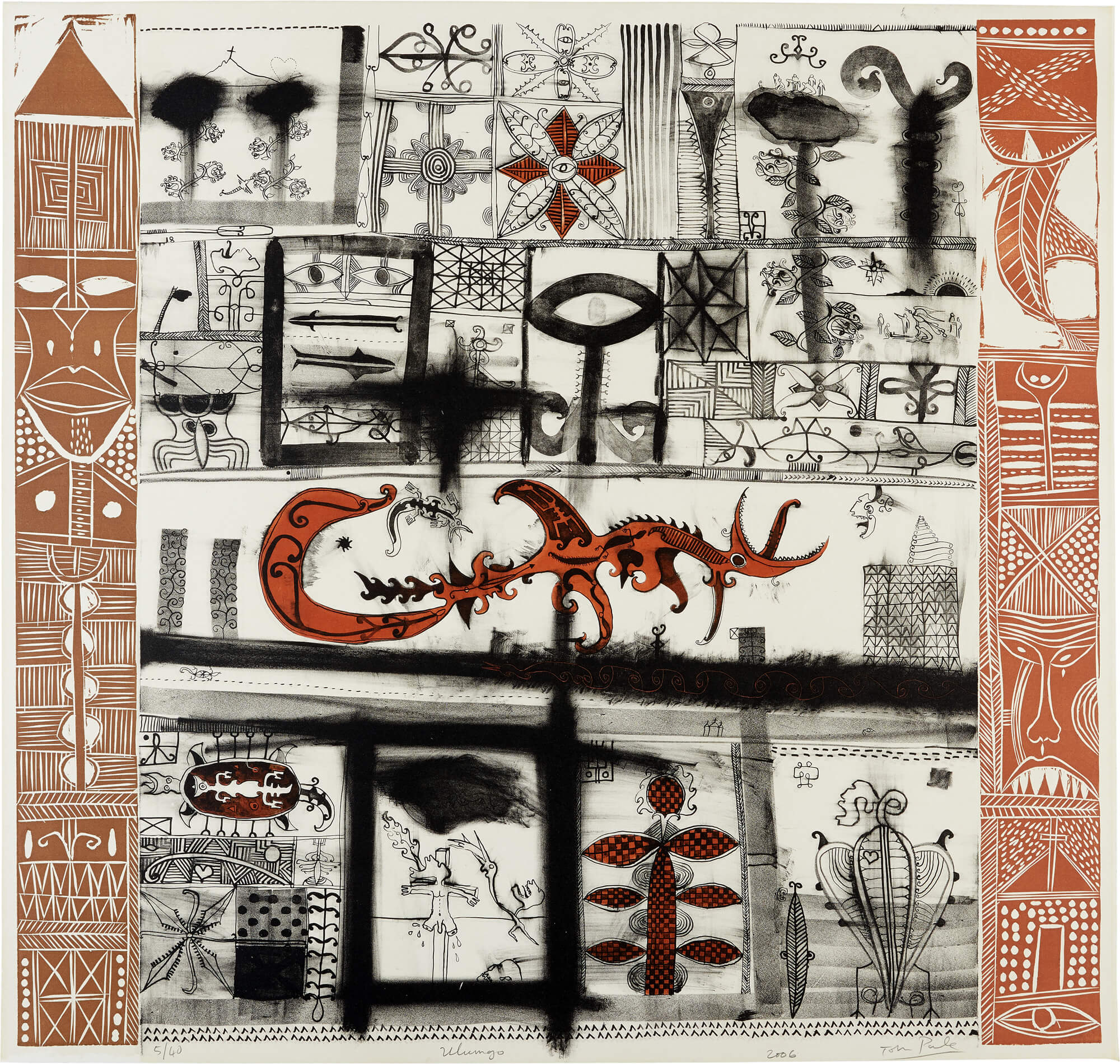

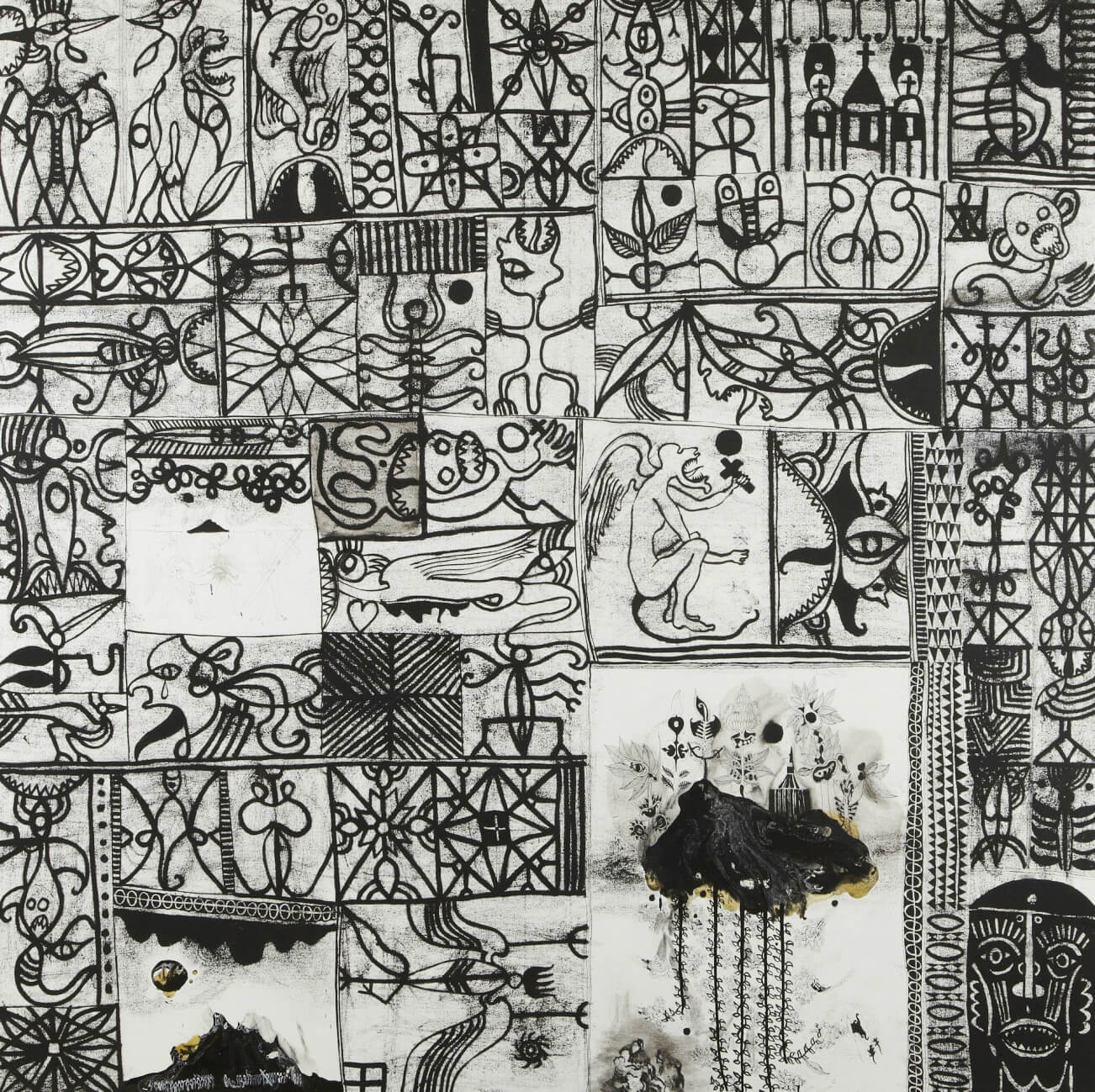

John Pule (*1962) was born on the Polynesian island of Niue and came to Auckland in New Zealand as a child with his parents. He is a writer and visual artist. His literary works, which have been in production since the 1980s, reflect the experience of migration and foreignness in a new country. His first visit to the home island of Niue in 1991 is followed by an intensive examination of its spiritual and material culture, in which the bark bast cloths provide a major incentive for formulation of his own visual language.

Level 2 | Tapa from Samoa and Tonga

Samoa and Tonga, where the bark bast cloths are still produced today for special private and official occasions and where they form an important part of the cultural identity, are the origin of exhibits with bold patterns accentuated by overpainting. On Samoa, the bark bast cloths are referred to as siapo, as soap elei when decorated on the basis of templates, and as soap mamanu when painted by hand. Grid structures are characteristic of both design forms.

From ancient times, the bark cloths became especially important on Samoa as bartering objects and as objects of value on the occasion of births, marriages and deaths as well as at when chieftain titles were awarded. To this day, they are considered to be a distinctive gift for special guests or for family members who live abroad and they are essential at official and private occasions.

On the islands of the Tonga archipelago, the tapa cloths are coloured predominantly using pattern boards or stencils. Here, the bark bast cloths have been stretched over the raised bar and the colour has been applied with impregnated cloths. In the further processing, specific aspects of the pattern have been accentuated or additional elements introduced. Tonga is the only region in the world where historic events have influenced the design of bark cloths. As such, Spitfire representations on a textile fragment from Sammlung Klein are reminiscent of the aeroplanes that the Tongan queen acquired to support the English in the Second World War. Today, bark bast cloths are no longer significant in everyday use on Tonga. However, as objects of value, they are still produced in large numbers and certainly for stock.

Level 3 | Niue, Fiji, Futuna

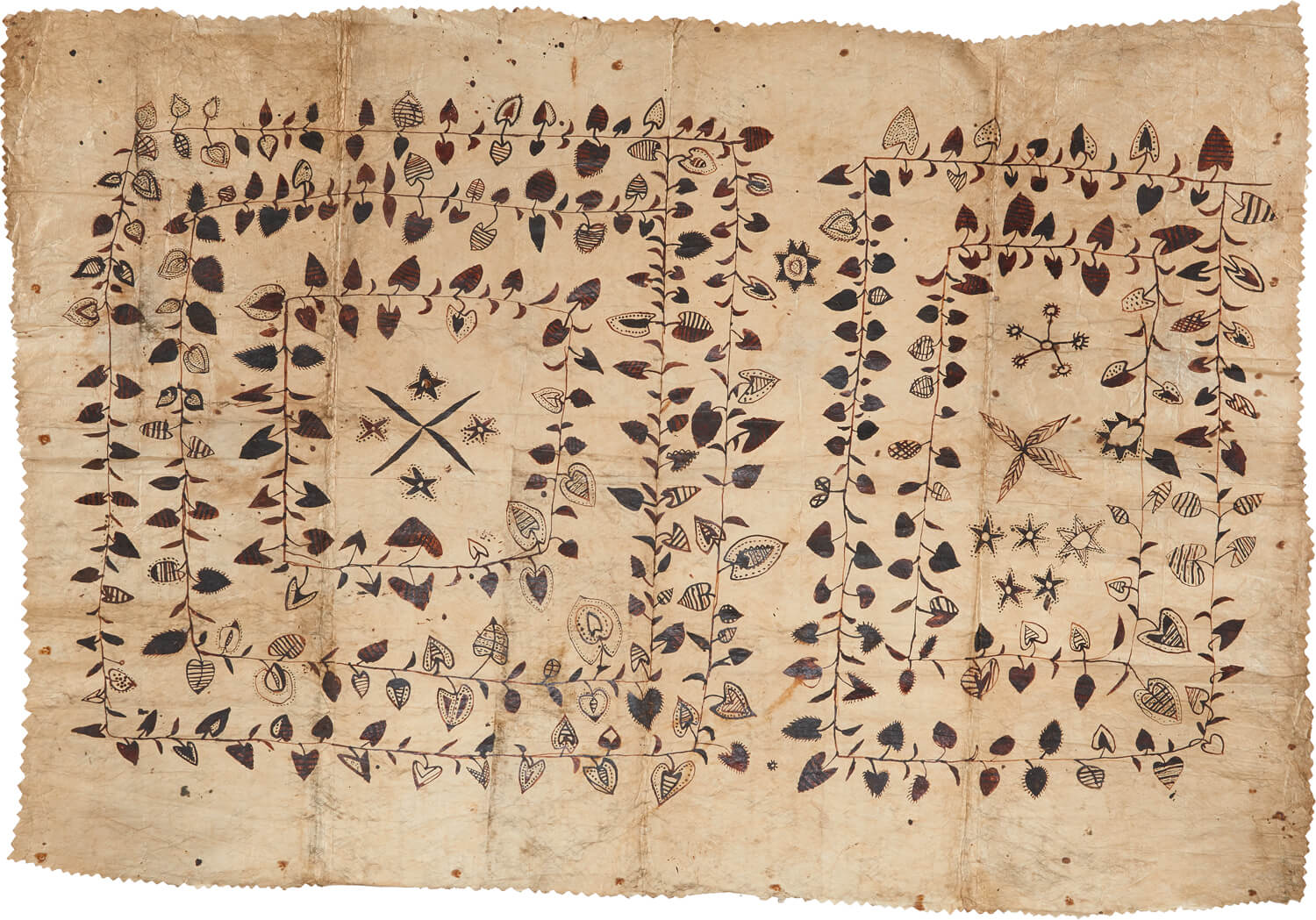

Tapa art on Niue is documented only between 1865 and 1900. Patterned tapa fabrics probably first came to the island with Samoan missionaries. The first discrete patterns are known from tapaponchos, which are cut on the basis of the Tahitian model.

The bark bast cloths from Niue were painted exclusively by hand, initially with free compositions. Since the 1880s and possibly under the influence of a local painting school, image structures have developed on the basis of grids. The significance of these works in the local cultural context remains unclear. Production of bark cloths was discontinued on Niue as early as in 1900. However, they have survived in museums and collections and remain an inspiration to descendants to this day.

On the Fiji Islands, the bark cloths – known here as masi – had many uses. They were used by men as loincloths or turbans. Oiled and smoked, they were the sign of a chieftain. They served as mosquito protection but also as flags to adorn people or weapons in dance, war and festivals, or as a medium of exchange within Fiji society to seal relationships between chiefdoms.

Relationships that have existed for centuries between the individual Fiji Islands, Tonga and Samoa have influenced the local tapa traditions. Stencils cut out of leaves were used for the design of patterned cloths. These generally helped to create serial decorations, which were combined with strips or abstract natural forms.

On Fiji too, the importance of tapa production has declined. However, there are still occasions today when large quantities of the fabric are presented.

The residents of Futuna and neighbouring island Alofi speak a language that is closely related to Samoan and also refer to bark bast cloths as siapo. It is therefore no surprise that some of their tapa production also follows the Samoan model: cloths produced jointly by two or more women and glued together are printed with templates and then painted by hand. For use as a dance apron – to this day the clear distinguishing feature of traditional dance groups – a lower horizontal strip remained unprinted and was designed freehand. The whole characteristic style of the decorations used here is in clear contrast with the overpainting of the preprinted cloth with bold lines.

In other patterns, wickerwork from the Micronesian Marshall Islands or even carpets of European origin have provided ideas for very distinct painting, comprising very complex compositions of patterns and among the most richly varied forms of decoration from the entire Pacific.