Spots. Stripes. Bands. And circles time after time, showing various centres in the image overall. Organic areas and lines, but also graphic patterns, set in contrasts of strong colours or in harmonious colour tones. Initially, we can describe the painting of the Australian Aborigines only in abstract terms. Yet their art is not without objective. It is a testament to an ancient culture, which has developed visual ciphers for interpretation of the real world.

#14

The Aborigines settled in Australia over 50,000 years ago and formed many language groups. All lived as hunter-gatherers. They shared the tenets of a world view that traced humans and nature to the same origins, namely the creative forces established in the land itself. Humans had special responsibility for the land, which they met through ceremonies and through sustainable everyday action.

Artistic forms of expression were an essential part of traditional life. They are handed down to the present day in the form of rock paintings and petroglyphs but – as ritually created ground pictures, as body painting or dance crests – they were mostly extremely transient. As many traditions were holy and secret, they remained largely unknown to the new European/American immigrants until the mid-20th century.

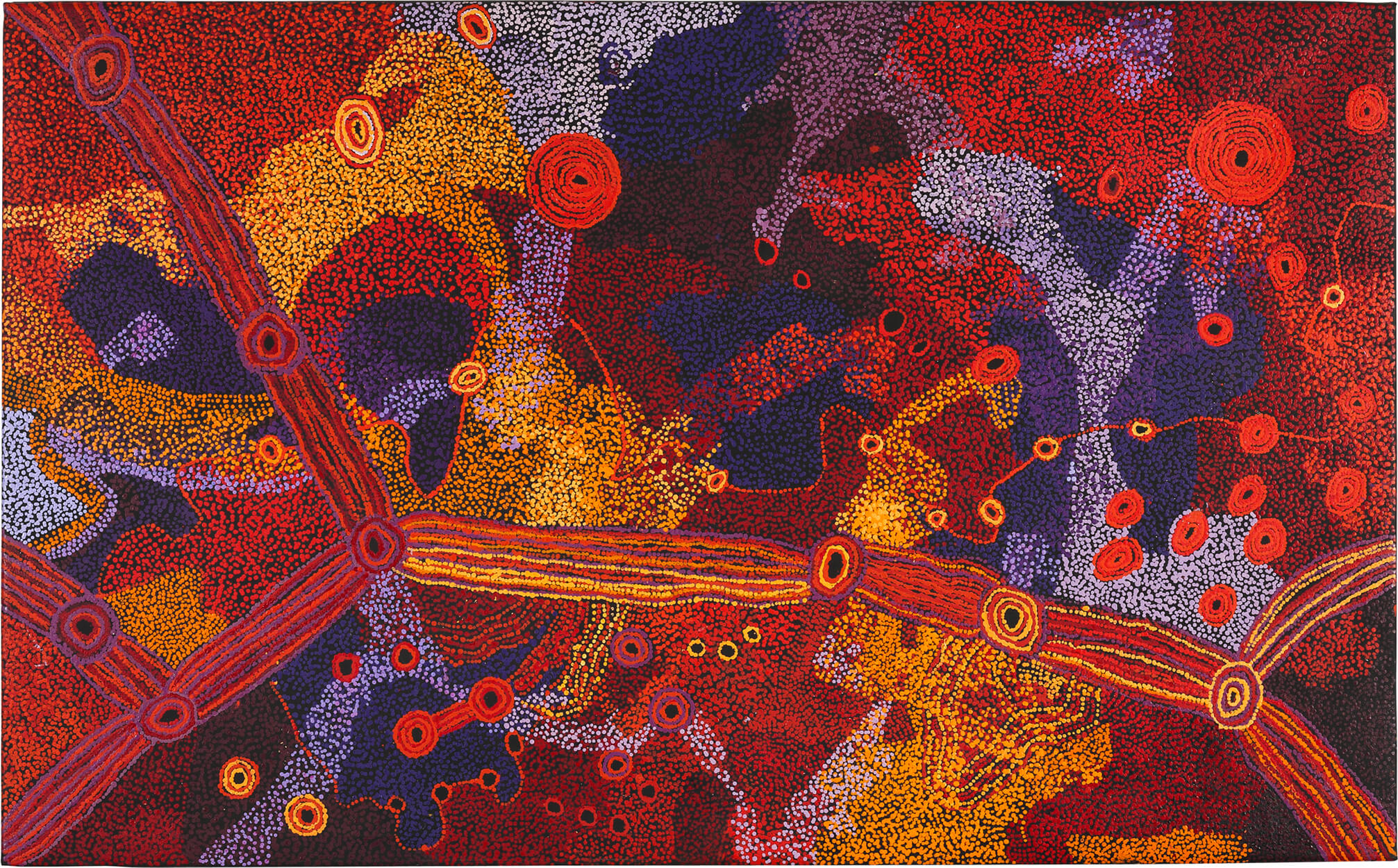

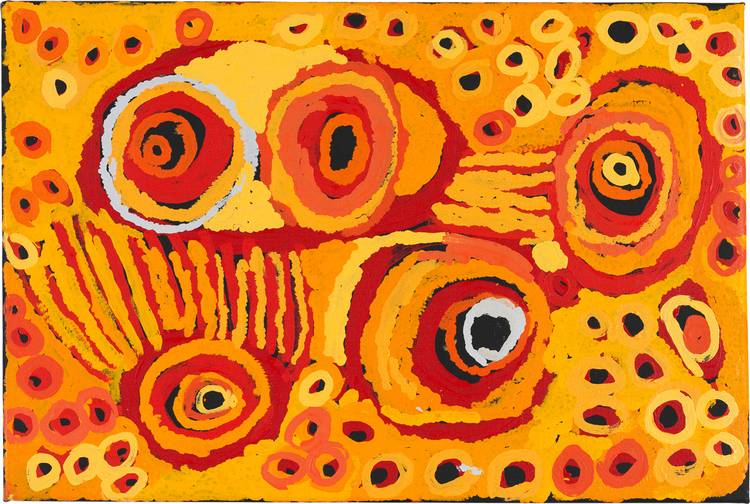

The use of industrial paints and modern, mobile primers goes back to 1972, when ritual specialists in Papunya began to convert parts of their special tradition into new image formats, which are set out like mythical maps. The basic subject was and is the land, the specific form of which – mountain ranges, lakes, waterholes or trees – stems from creative beings. Even today, their power must and can be activated in these places for the present time. To the artists, the right – true – implementation of their respective specific traditions is more important than aesthetic criteria. However, this does not prevent them from experimenting with different artistic possibilities and forging new paths.

#TOUR

LEVEL 1

On level 1 works are assembled, which refer in their creative form to the beginnings of Aborigine painting in the 1970s. These are contrasted with five works on wood by Ngipi Ward (Patjarr, Kayili Artists) and Kanta Kathleen Donnegan (Tjuntuntjara, Spinifex Art Projects). The works, which were created in 2013 and 2014, demonstrate the spectrum established even in the 1970s between comprehensive „documentation“ of a region with its sacred places and the specific local view and its seasonal changes. Ngipi Ward’s pictures relate to the Kuluntjarra salt lake and to the changing vegetation of the Gibson Desert, whilst Kanta Kathleen Donnegan’s painting represents the paths of the ancestor creators around Kapi Piti Kutjara.

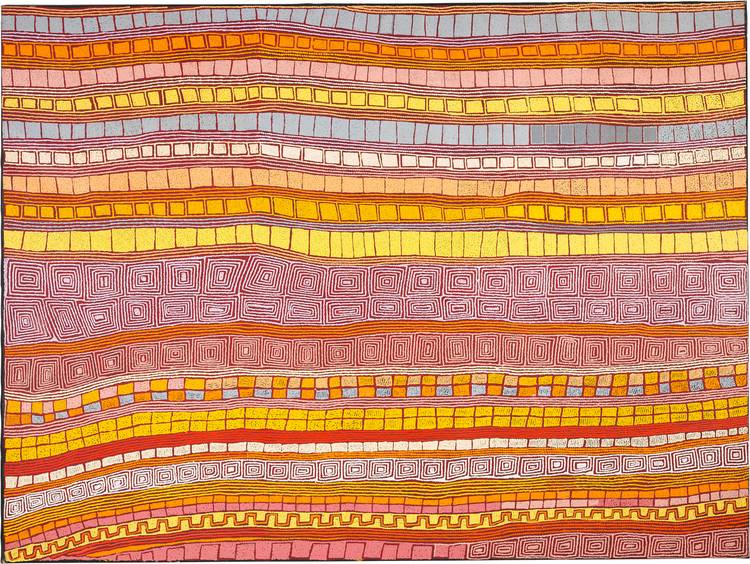

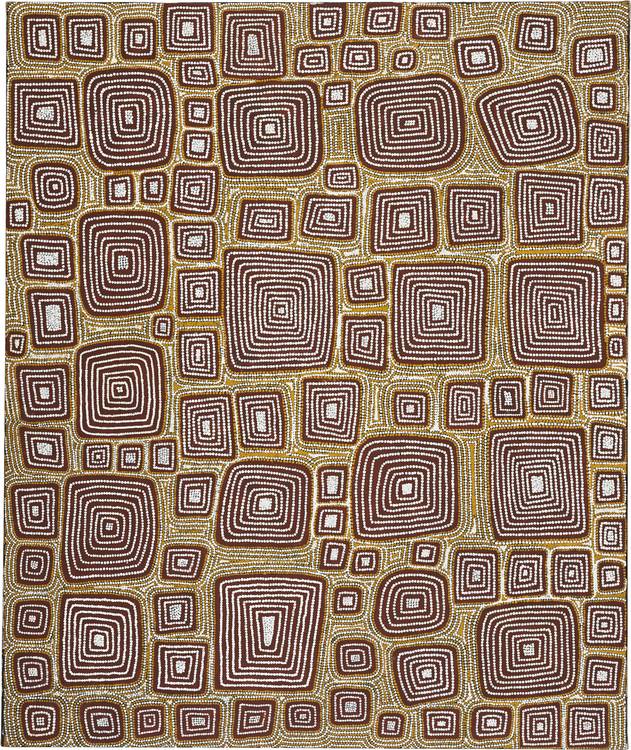

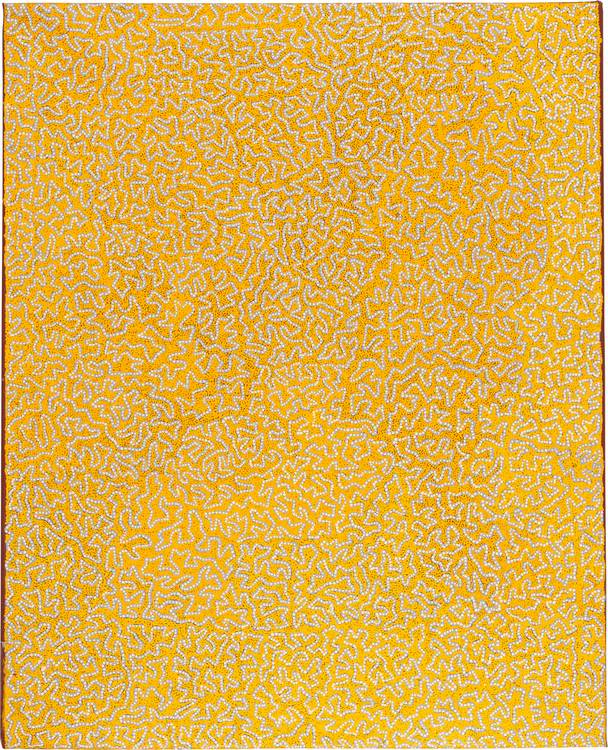

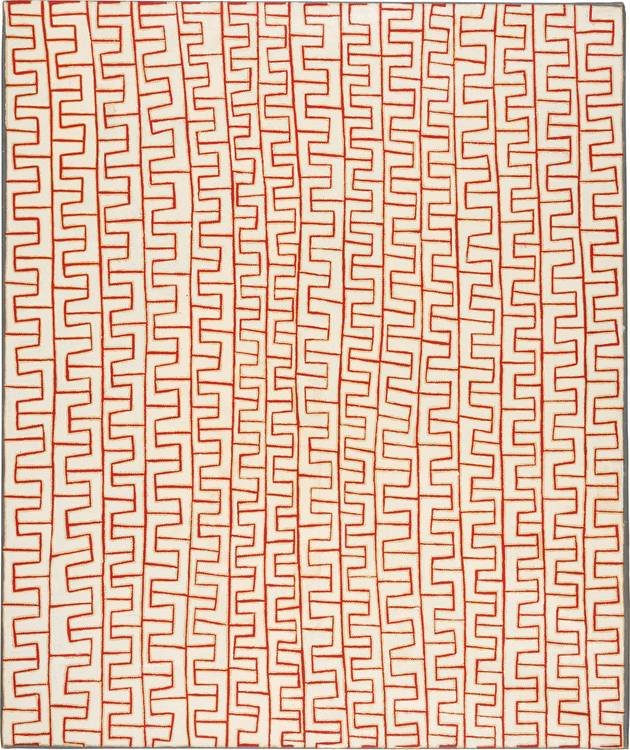

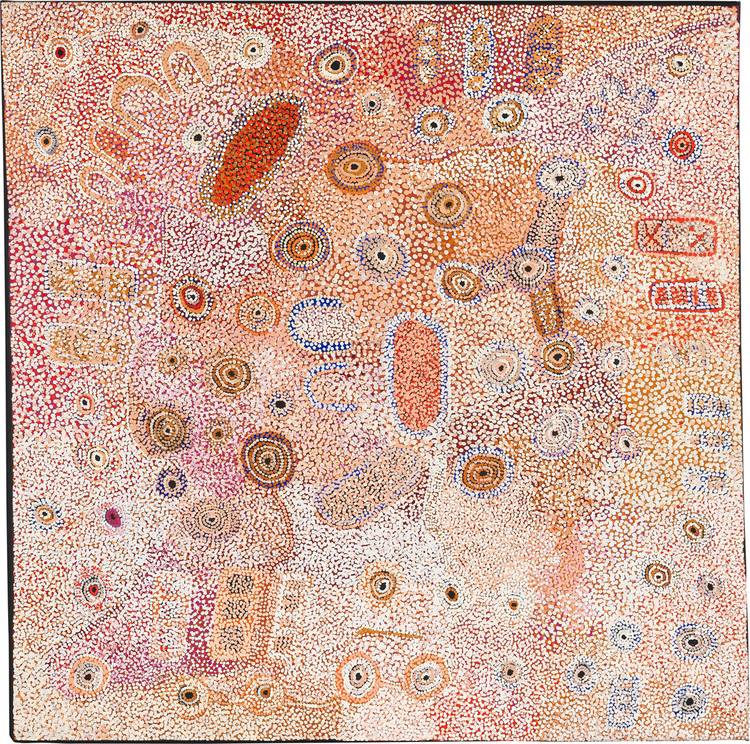

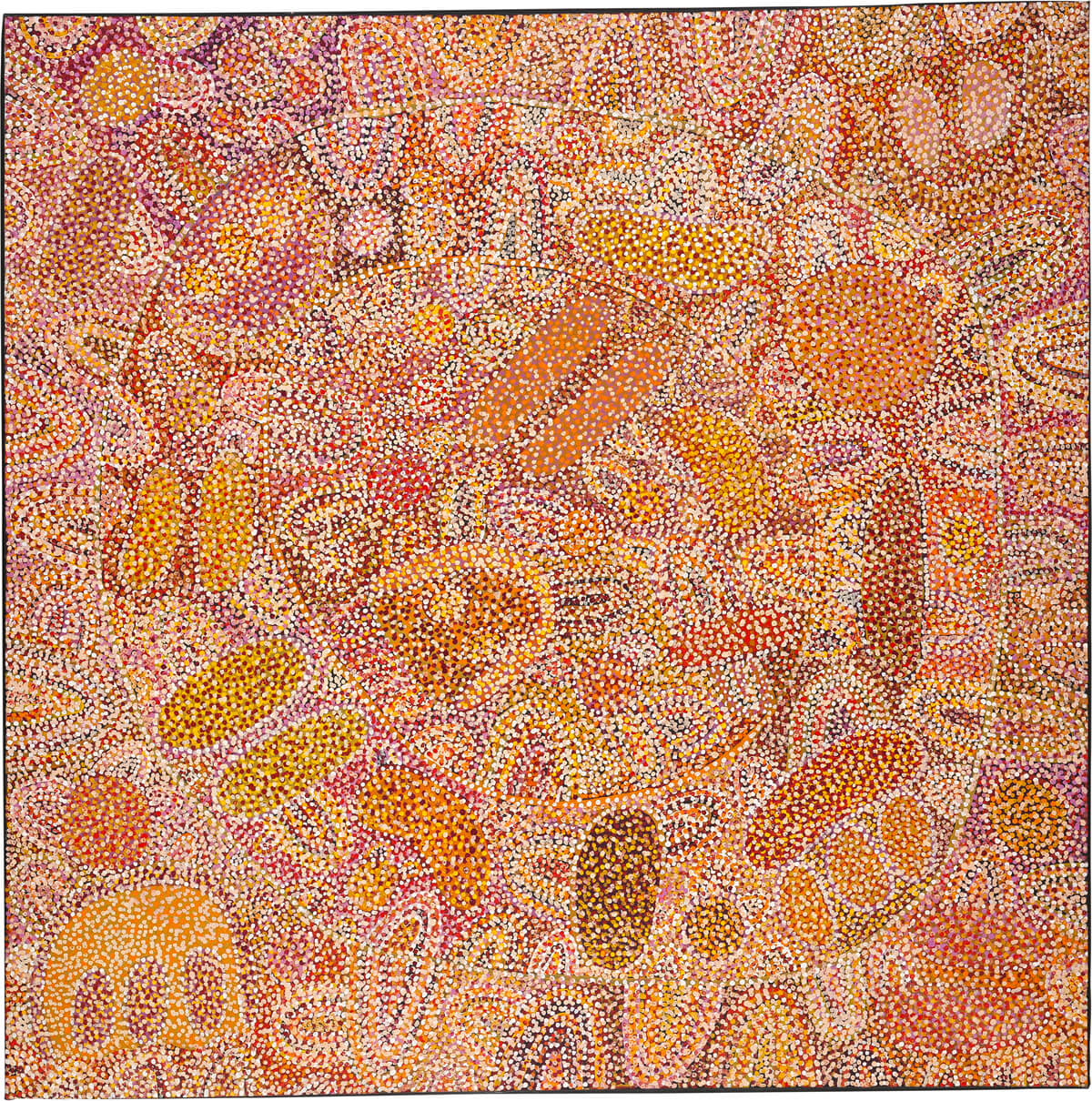

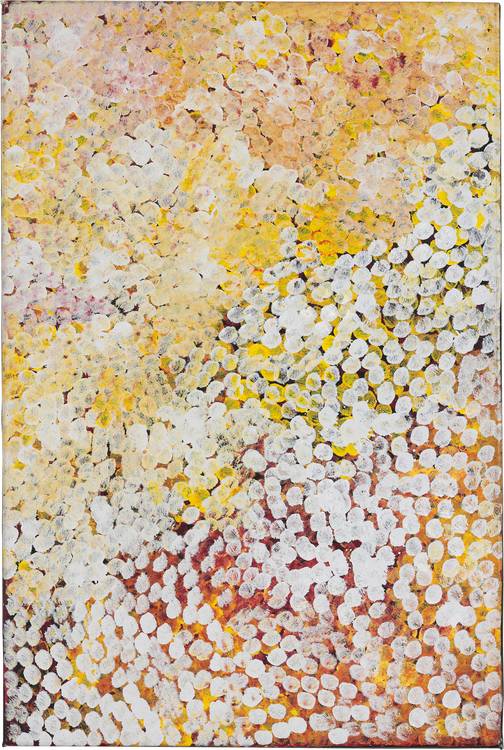

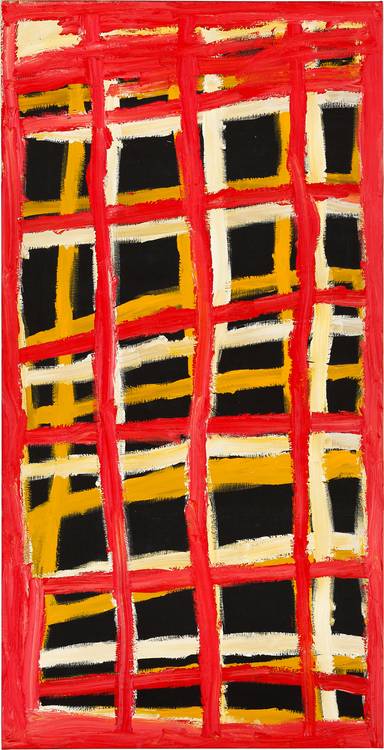

Contrasted with these are works by painters from different regions. Almost without exception, they are dedicated to the major subject of the tingari cycle, which „belongs to all men“ and which describes both the creation of the land and many cultural traditions. The sculptures can convey scenic attributes or movement through lines, precise dotting or structures in the paint application. This is how George Yapa Tjangala constructs his work on the rock holes of a secret tingari site in Tarkulgna from rectangular shapes and with a conservative pallet. More intense in colour is the sculpture by Patrick Tjungurrayi, created in 2008. In his journey to Myililli, he uses a finely graduated pallet of yellow and orange tones contrasted with pink and light blue/grey. With dots, he forms irregular stripes, which he varies internally with rectangles. By illustrating their root system, Joseph Jurra Tjapaltjarri conveys with few colour nuances and differently curved, almost spidery lines the wealth of edible tubers that was available to the tingari women at their resting place in Yunala. Ray James Tjangala gives an almost serial impression to his representation of tingari men’s storage locations north and west of Kintore, where they dug up the roots of the bush bananas commonly found here.

LEVEL 2

A large proportion of the works on level 2 were painted by women. They have their own pictorial traditions and content, focus on the fertility of the land, take up specific forms of body painting, or refer to dances that are associated with sacred places.

From Amata, the Tjala Arts art centre, come pictures by Sylvia Ken and a communal work by sisters Yaritji Young, Tjungkara Ken, Freda Brady, Sandra Ken and Marinka Tunkin.

The content of the painting by Silvia Ken is the story of the Seven Sisters, which is portrayed in many women’s dances and associated with the Seven Sisters of Pleiades. The subject of the communal work is the tjukurrpa of the honey ant.

The pieces by Ngupulya Pumani and Tuppy Ngintja Goodwin, both of whom work in Myillili in the art centre Mimili Maku Arts, refer to the tjukurrpa of an important foodstuff for the nomadic Aborigines: the witchetty grub. Whereas Tuppy Goodwin also shows the wider surroundings around the ceremonial site of Antara, Ngupulya Pumani incorporates into her composition the women whose dances cause the grubs to multiply: represented in the form of semicircles highlighted by the shimmering of the dots.

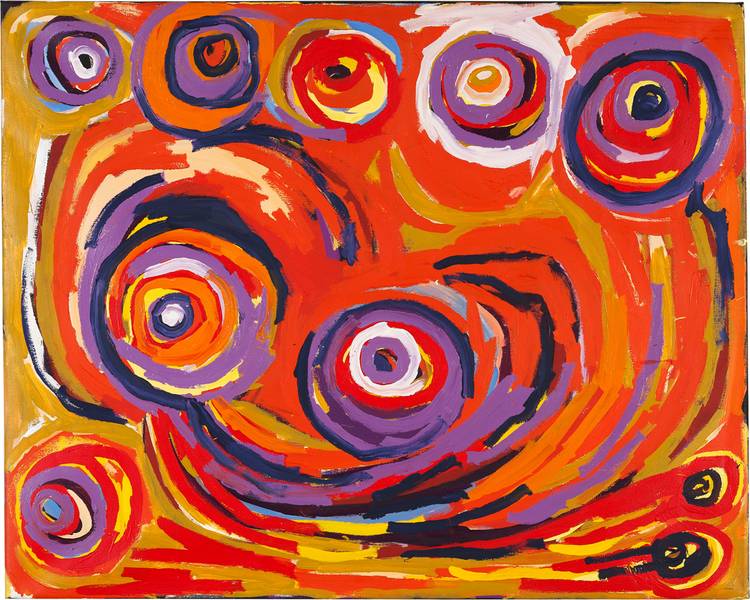

Alongside two paintings by the now legendary Emily Kame Kngwarreye from Utopia, the pictures of Sally Gabori and May Moodoonuthi in particular display a very individual style. Both belong to a senior group of painters on the Mornington Islands in Northern Australia. Like Emily Kame Kngwarreye, they came into contact with canvas and paints only at an older age and burst open our idea of the nature of Aborigine painting. They work with powerful brushstrokes and strong colours: May Moodoonuthi in connection with traditional body painting and grief scars; Sally Gabori in memory of the island of her childhood, which she translates into painting with layers of colour and big gestures.

Against the strongly coloured paintings, one series of works sets its own accent in the exhibition: they have a graphical nature. Their effect is characterised by the black/white contrast – painted by men and referring to the Tingari cycle.

A number of works on level 2, which come from Kimberley in the north of Western Australia, appear similarly reduced in colour. The late Rover Thomas and the artists still active from Warmun blend their own colours from local ochre, charcoal and pipeclay. The otherwise frequently used dots are used only sparingly in their work, to delimit areas. Their subject is also the land, its power, its “bones”, often coupled with personal, emotional experiences or with historic events that resonate in the works but are revealed only rarely.

With the selection of works, the exhibition aims to show the vitality in the development of Aborigine painting. The artists do not content themselves merely with reproducing painting traditions of local origin; more than ever, they are in dialogue with each other and with urban centres and they are challenged to develop their own forms of expression from their conventions, from their visual and auditory memory, and from external stimuli.

For this exhibition, a 60-page catalogue, Hängung #14 – NEUE BILDER Malerei der Aborigines (Hanging #14 – NEW PICTURES, Painting of the Aborigines), has been published with a text by curator Dr Ingrid Heermann of Stuttgart.

60 pages. 8,00 EUR.