The two artistic positions of Edward S. Curtis and Will Wilson are separated by around 100 years and reflect different perspectives on the representation and perception of the indigenous population of North America in the exhibition entitled …als würden allein diese Bilder bleiben (…As if Only These Pictures Remained). Their works emerge in relation to popular notions of “the Indians”, which are generally shaped by the stories of Karl May and their film adaptations.

#26

Which images come to mind, when we hear on the one hand about “the Indians” and on the other hand about “native Americans”? Even the different names for the first Americans evoke different mental scenarios. You probably initially think of childhood games, books, films with Winnetou and Old Shatterhand as the heroes, or – like today’s children – tales of Yakari that are familiar from comic films. The second term reflects a different, contemporary perspective, one of which there are far fewer pictures than of the former.

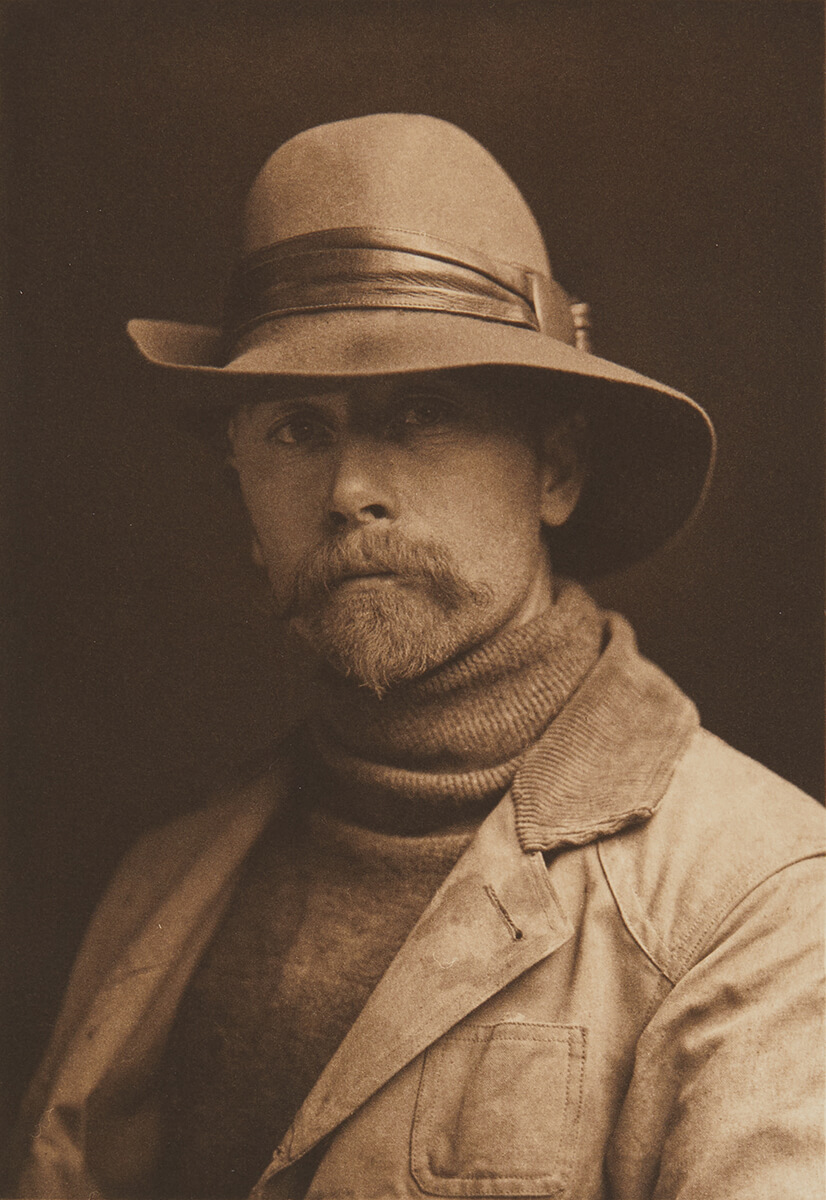

Shaped over a long period, where do the notions of “the Indians” come from? How are they viewed from the perspective of a present-day indigenous position? In the exhibition ... als würden allein diese Bilder bleiben (…As if Only These Pictures Remained), KUNSTWERK allows historical and contemporary photographs to speak. It creates a dialogue between the photogravure, photographic and goldtone prints of Edward S. Curtis (1868 – 1952) and the works – presented in Western Europe for the first time – of multimedia artist Will Wilson (*1969), who lives in Santa Fe and is himself a member of the Navajo/Diné nation.

#TOUR

Ebe

Level 1

ne 1 | NINA RÖDER

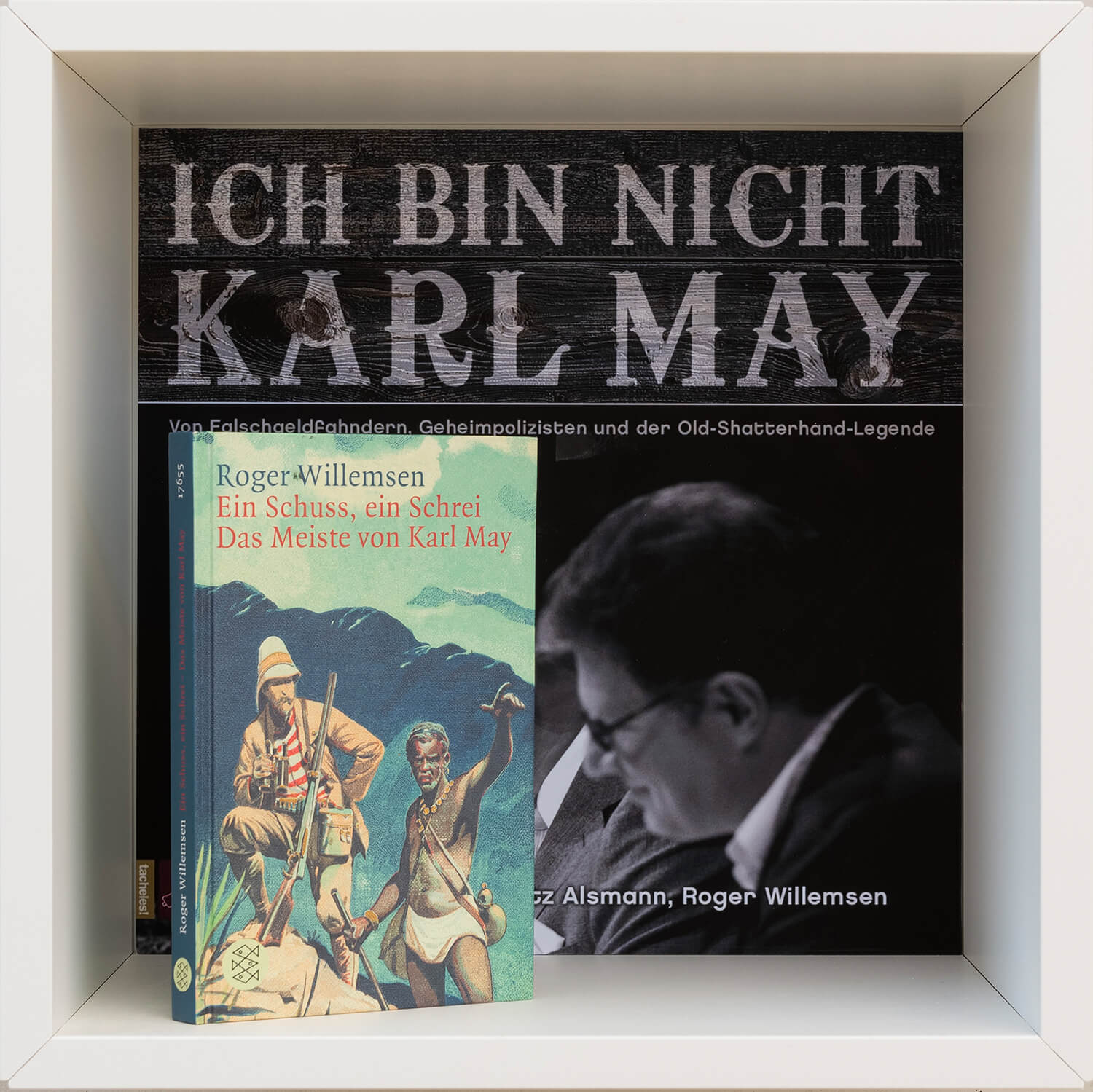

All who come to the exhibition at KUNSTWERK will, to some extent, arrive with their own “mental images”. In our society the notion of “the Indians” is generally shaped by the stories of Karl May and their film adaptations from the 1960s and 70s. Even though we know they are based on literary fiction and follow stereotypes to a great extent, they nonetheless remain a part of our own identity.

The presentation on Level 1 reflects conversations with guests at KUNSTWERK during the preparation of the exhibition. A number of visitors provided exhibits that represent their spontaneously expressed associations. In an entirely random, exemplary way, these demonstrate the familiar but also give rise to many new discoveries.

Ebe

Level 2: EDWARD S. CURTIS

ne 1 | NINA RÖDER

With his 20-volume encyclopaedia, The North American Indian, published between 1907 and 1930, Edward Sheriff Curtis created an unparalleled life’s work, with which he registered his place in the history both of photography and of the American nation.

The photographer was born in Wisconsin in 1868. At the age of 23 he moved to Seattle, where he operated a portrait and landscape photography studio. From the end of the 19th century he dedicated his work to the Indian cultures of North America. He visited over 80 tribes in the reservations of the American West and took more than 40,000 photographs. Together with assistants and interpreters, he compiled thousands of pages of information about the life of the Indian communities, their social structures, customs and traditions, their religious beliefs and craftwork. On wax cylinders he recorded songs and the different languages, which he translated into musical notation and phonetic symbols.

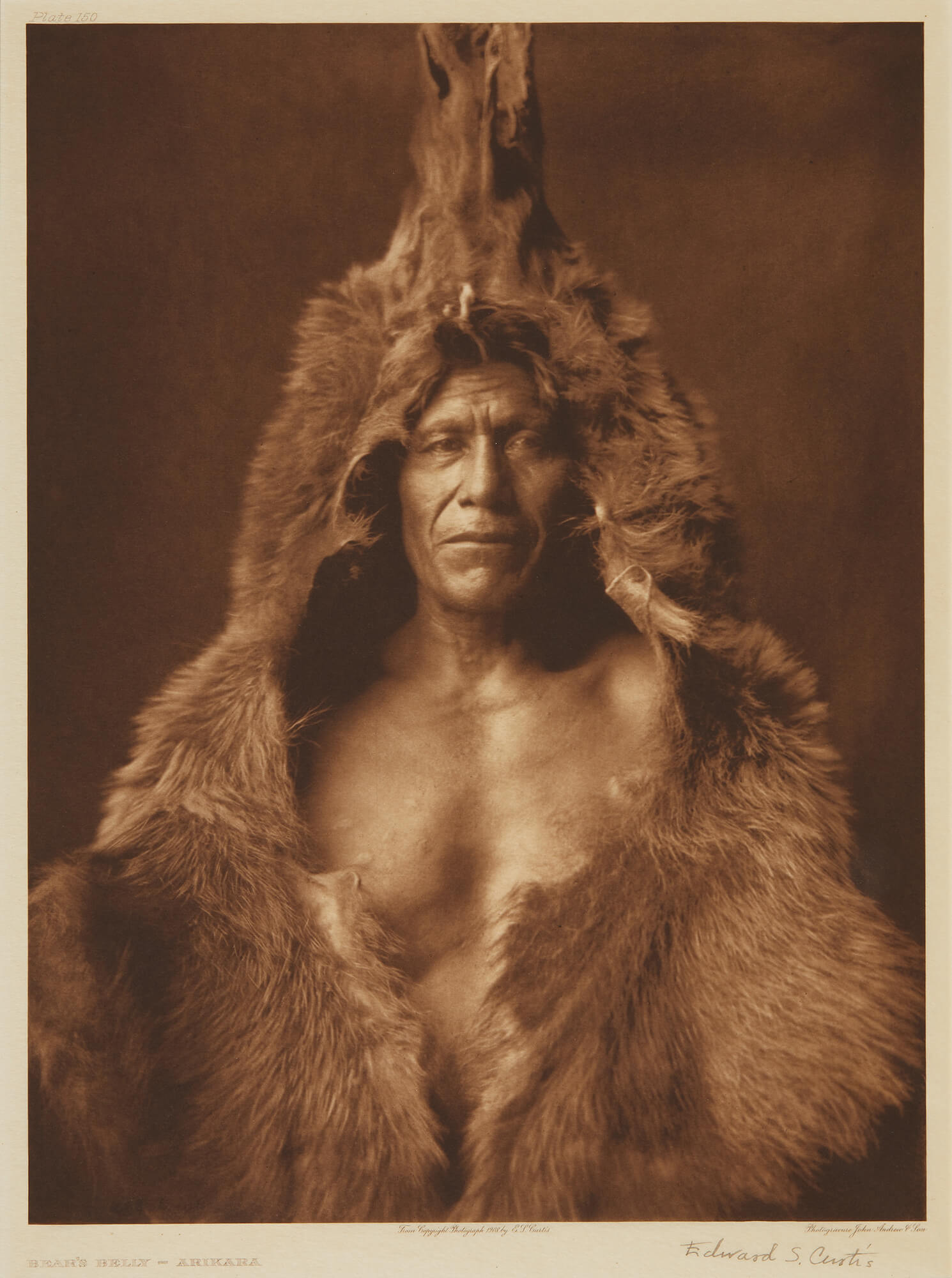

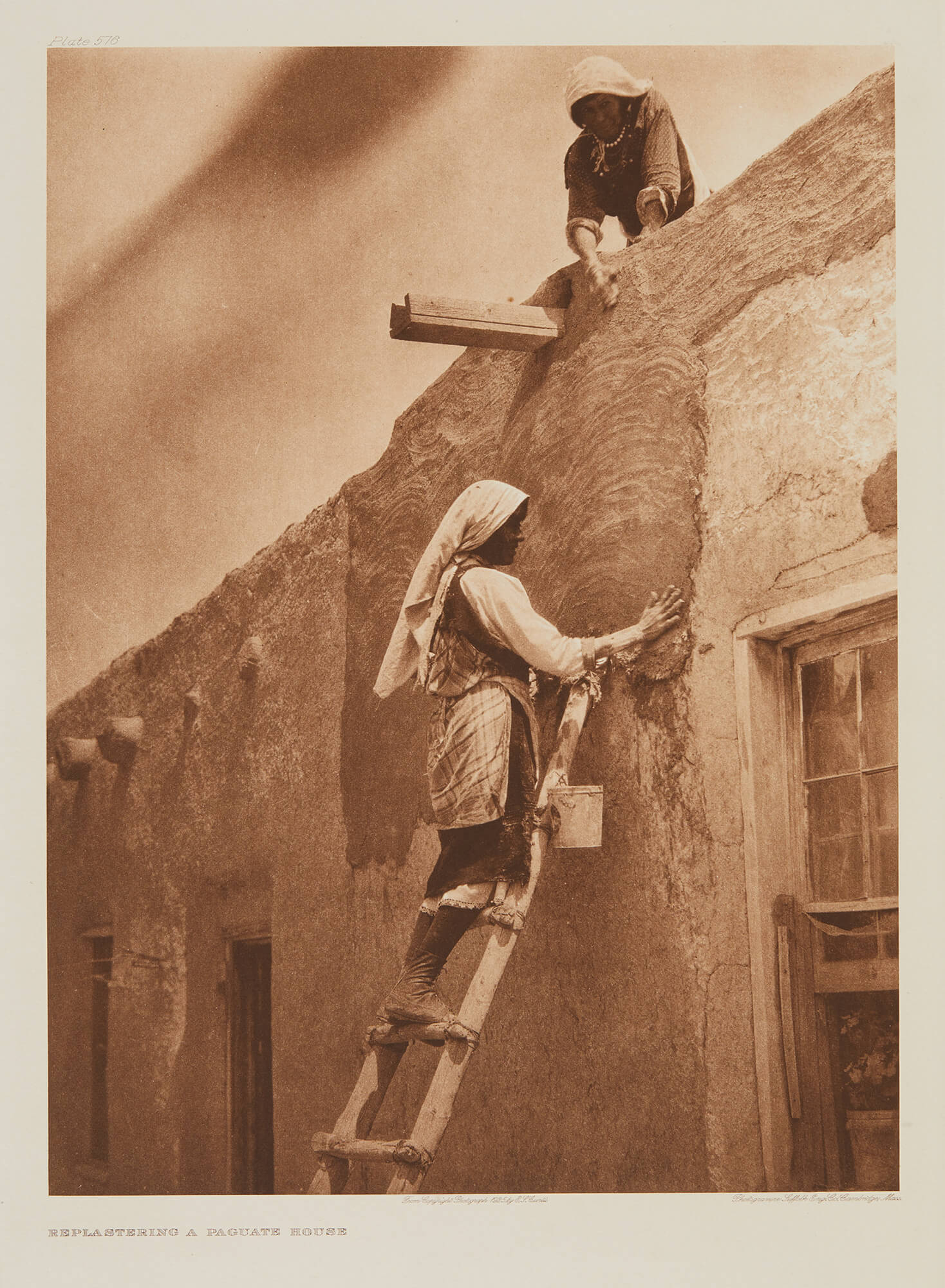

Curtis summarised his field research in high-quality text/image volumes, which were published with the financial support of railway and banking tycoon J. P. Morgan and his son. These are dedicated in part to individual but mostly to multiple indigenous groups, and each contains 75 illustrations. With the individual volumes, Curtis issued portfolio folders with 35 selected photographs in 40 x 30 cm format. Like the illustrations in the books, these were produced using the intaglio technique of photogravure.

Most of the exhibits in the KUNSTWERK exhibition come from 12 of the total of 20 portfolio folders. Pictures in smaller formats are taken from dismantled text/image volumes.

In the further examination of his work, the written records of Edward S. Curtis about the indigenous communities of North America are outshone by the impressive effect of his photographs. Initially, it is picturesque, atmospheric photographs that bear witness to a level of sympathy and appreciation of the Indian population and culture that was not self-evident at that time. In view of the reality in the reservations, increasing assimilation and the influence of modern life, Curtis the photographer went beyond the purely documentary. He achieved this by creating atmospheric and carefully composed images in the tradition of photographic-artistic pictorialism, which essentially evoke the conditions before the cultural change as a result of European-American influences.

Rare goldtone prints are a highlight in the presentation of the works by Edward S. Curtis on Level 2. Reproduced on glass plates, the photographs are backed by a gold-coloured, shimmering coating, which gives the two-dimensional photography an exceptional depth and transparency. Of particular note here is the picture entitled The Vanishing Race. Curtis himself placed the subject, photographed in 1904, as the first illustration in his first portfolio folder. In a programmatic way, it therefore underlines the fact that he – in complete agreement with many contemporaries – could see the Indian cultures vanishing. He wanted somehow to record what still existed, but was absolutely guided by his own concept of what was “typically Indian”.

Ebe

Level 3: Will Wilson

ne 1 | NINA RÖDER

In his projects, multimedia artist Will Wilson, who was born in 1969 and lives in Santa Fe – himself a member of the Navajo/Diné nation – responds to the artistic heritage of Edward S. Curtis. He contrasts the works with a contemporary narrative that not only testifies to the survival of Indian tradition and the self-determined identity of native Americans based on this, but that also looks to the future beyond the present day.

Wilson deliberately picks up on traditional image patterns and historic processes in photography, but he gives them a contemporary substance. Specifically by building a bridge between past and present, he is able to occupy a position that places the significance of the indigenous tradition in a new light.

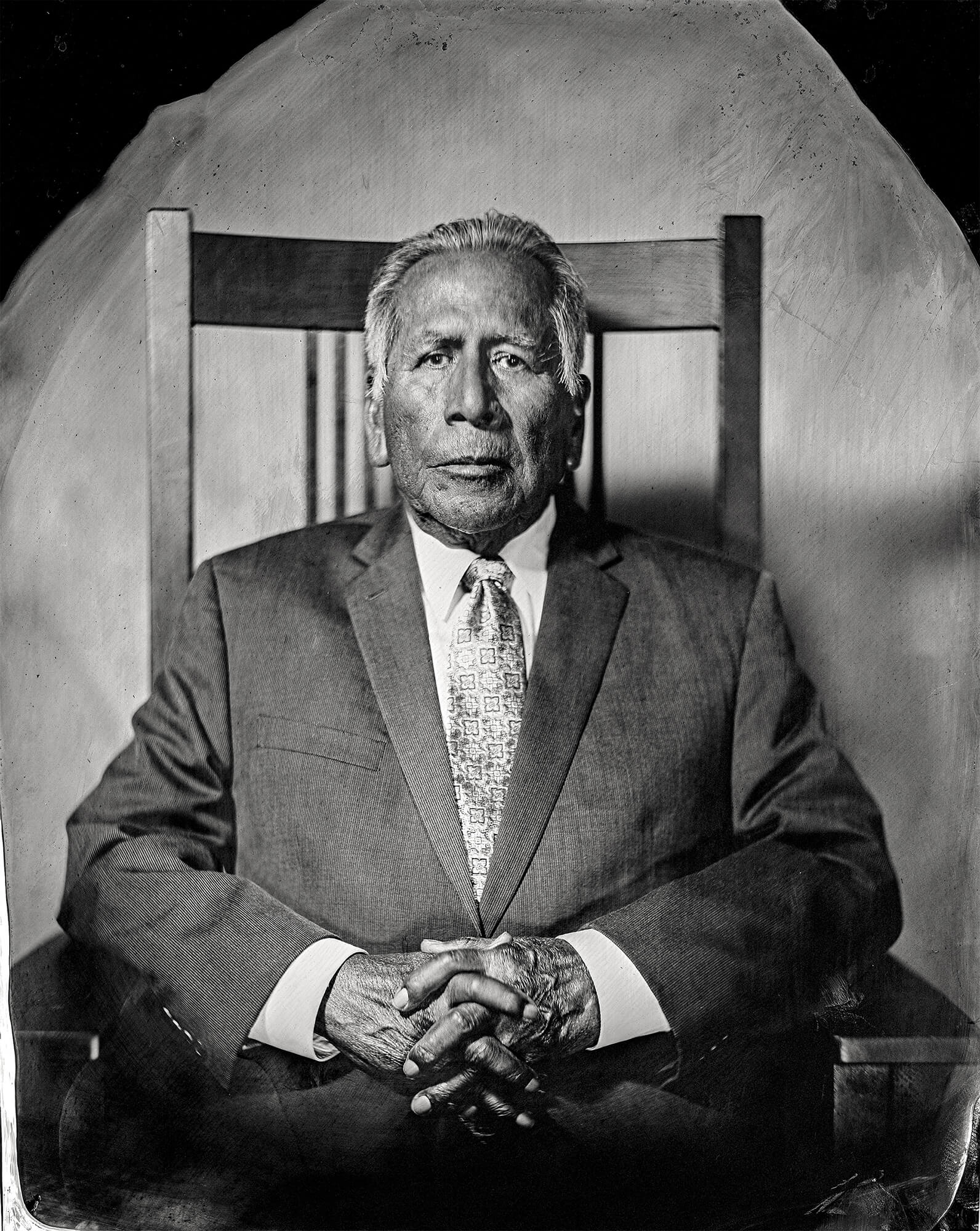

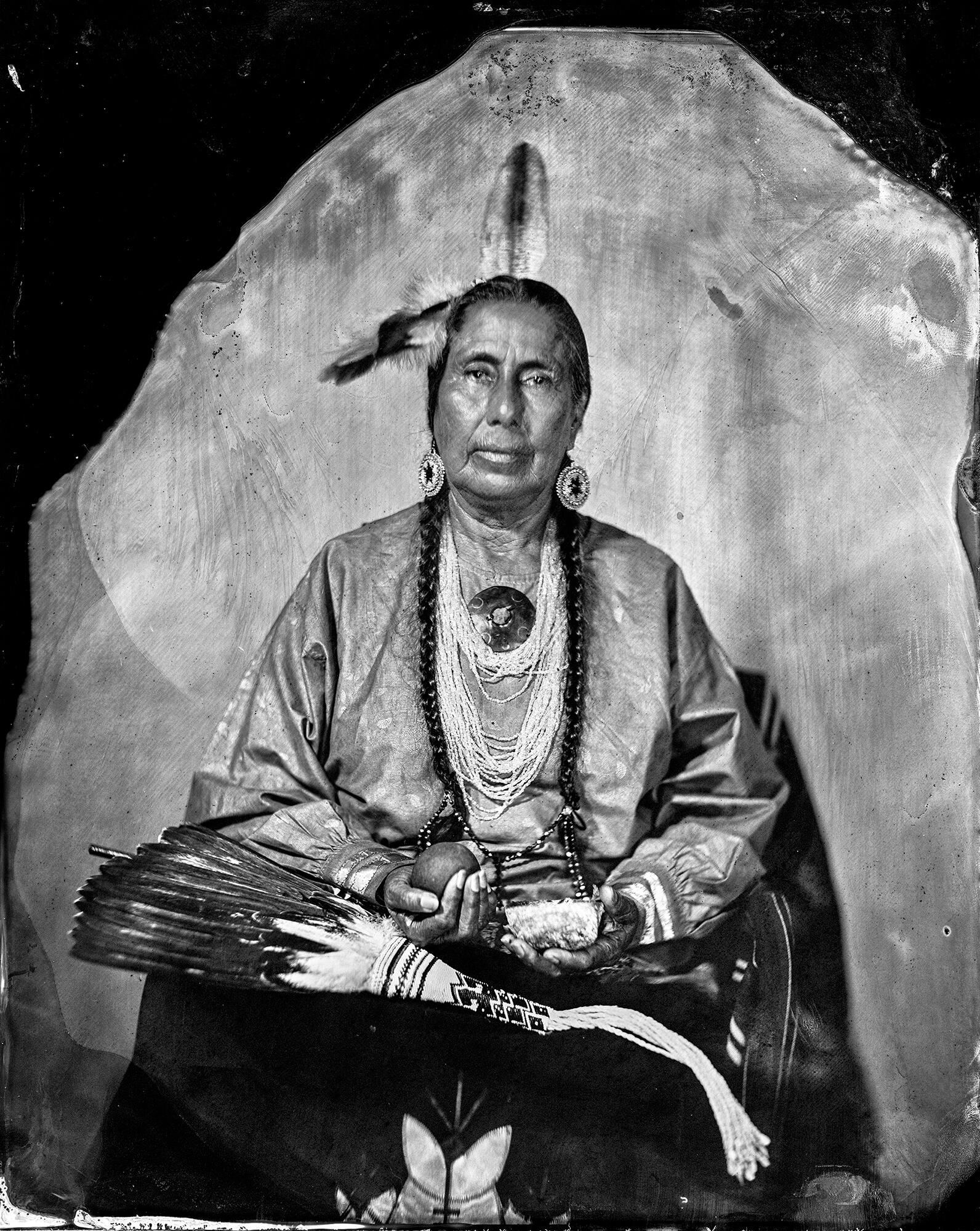

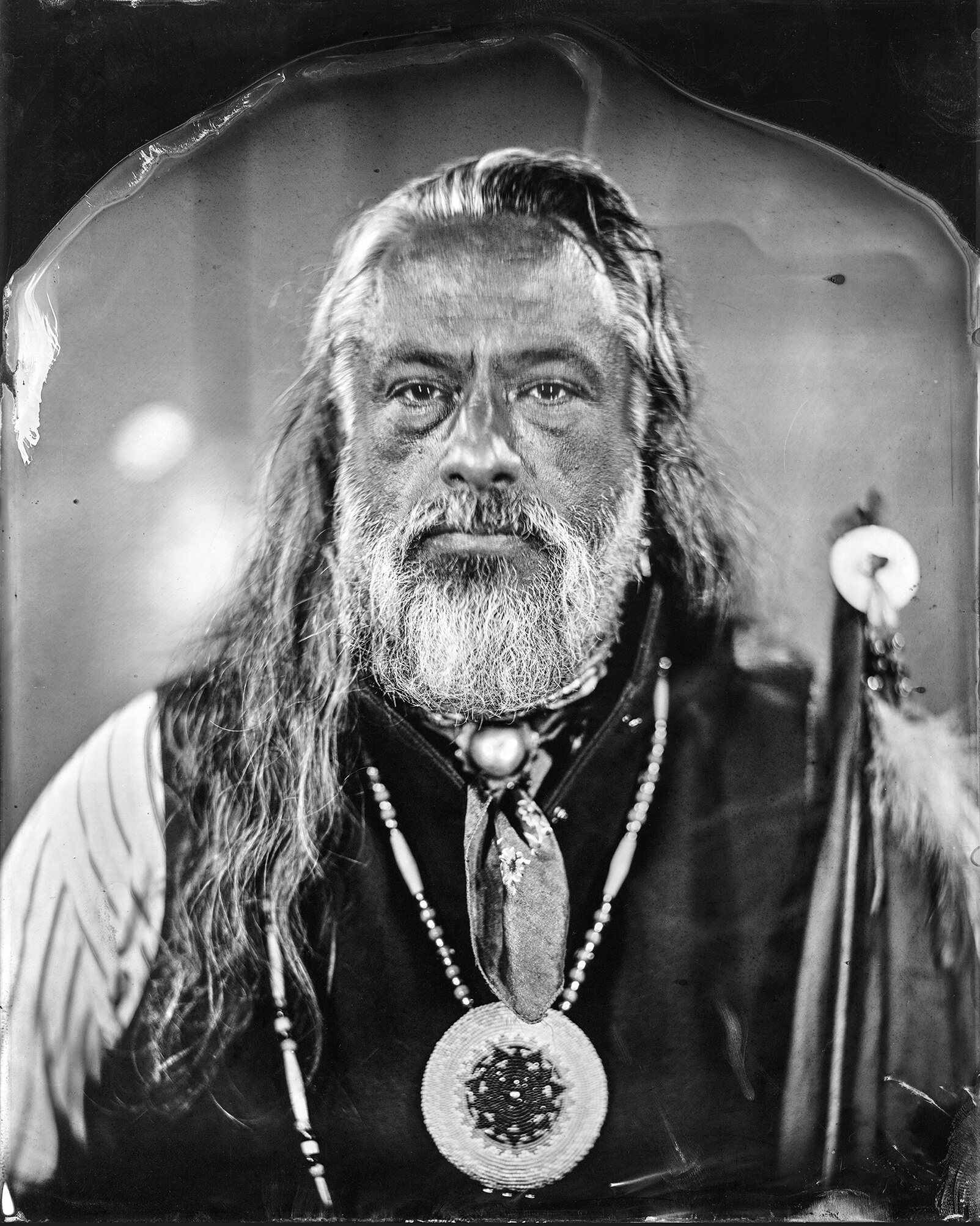

Will Wilson began his Critical Indigenous Photographic Exchange (CIPX) project in 2012. In cooperation with indigenous communities and various museums, he invited descendants of those portrayed by Edward S. Curtis to speak about themselves and their view of the ongoing, living tradition of Indian culture. For the photographs that he takes here, he uses the historical wet-plate collodion scan process, which – in a similar way to the subsequent Polaroid – is developed directly on the coated metal plate. Of critical importance in this is a new understanding of his role as an author. It is no longer the photographer who determines the artistic representation, as Curtis once did; all participants decide for themselves in which clothing and with which attributes their picture is taken, and which stories they tell. It is vitally important that they receive the original tintype immediately on the spot. In return, Will Wilson gains the right to use the scanned images for his artistic work.

Once again, the Talking Tintypes in the exhibition highlight Will Wilson’s position as a 21st-century artist as well as the dialogical principle of the CIPX project. With an app that can be downloaded using the QR code shown here, a smartphone can be used to access video sequences by pointing the smartphone camera at one of the photographs. Will Wilson’s Talking Tintypes convey personal encounters with the depicted participants by linking their voices and actions with the respective present lifeworld of the viewers.

Will Wilson initially came to prominence in the United States with the works from his Auto Immune Response (AIR) series, which began in 2004. Large-scale image panoramas and video works show a male protagonist in landscapes where all life is extinguished. In these, Wilson reflects on the consequences of the extensive uranium mining in the Navajo Nation Reservation from 1942 until the 1980s, as well as referring to the current alteration of the environment as a result of climate change. The image concepts of the vast landscapes and the interior photographs of a hogan – the traditional Diné dwelling – furnished with modern equipment reflect a current indigenous perspective, which addresses questions on a global scale with both inherited knowledge and the latest technology.